Himalayas

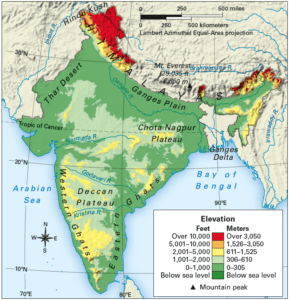

The Himalayas, or Himalayas, is a mountain range in Asia, separating the Indian subcontinent from the Tibetan subcontinent. The space contains some of the highest mountains on Earth, including the highest, Mount Everest; More than 100 peaks are found more than 7,200 m (23,600 ft) above sea level in the Himalayas. The Himalayas border crosses five countries: Nepal, China, Pakistan, Bhutan, and India. The sovereignty of the Kashmir region is disputed between India, Pakistan, and China. The Himalayas are bordered in the northwest by the Karakoram and Hindu Kush regions, in the north by the Tibetan Plateau, and in the south by the Indo-Gangetic Plateau. Some of the world’s largest rivers, the Indus, the Ganges, and the Tsangpo-Brahmaputra, originate near the Himalayas and their combined waters are home to about 600 million people; 53 million people live in the Himalayas. The Himalayas have greatly influenced the culture of South Asia and Tibet. Many Himalayan mountains are sacred to Hinduism and Buddhism. The peaks of many of them – Kangchenjunga (on the Indian side), Gangkhar Puensum, Machapuchare, Nanda Devi, and Kailash in the Tibetan TransHimalaya – are undeniable.

Raised by the subduction of the Indian tectonic plate beneath the Eurasian plate, the Himalayan range extends from west-northwest to east-southeast in an arc of 2,400 km (1,500 mi) length. Its western anchorage, Nanga Parbat, is just south of the northern reaches of the Indus River. Its eastern anchorage, Namcha Barwa, is immediately west of the Yarlung Tsangpo River. The width varies from 350 km (220 mi) in the west to 150 km (93 mi) in the east.

Key Features and Geography

The Himalayas consist of four parallel mountain ranges from south to north: the Sivalik Mountains in the south; the Himalayas; The Great Himalayas, the highest in the middle; and the Tibetan Himalayas in the north. The Karakoram is often considered separate from the Himalayas.

Among the great peaks of the Himalayas are the 8,000 m (26,000 ft) peaks of Dhaulagiri and Annapurna in Nepal, separated by the Kali Gandaki Gorge. The gorge divides the Himalayas into western and eastern parts, both ecologically and quantitatively – the pass at the head of Kali Gandaki, Kora La, is the lowest point on the ridgeline between Everest and K2 (the highest of the Karakoram range). To the east of Annapurna is the 8,000m (5.0 mi) peak of Manaslu and across the Tibetan border is Shishapangma.

To the south is Kathmandu, the capital of Nepal and the largest city in the Himalayas. To the east of the Kathmandu Valley is the Bhote / Sun Kosi River Valley which originates from Tibet and is the main land route between Nepal and China – Araniko Highway / China National Highway 318. More to the east is Mahalangur Himal and four which. the biggest road in the world. The six highest mountains in the country, including the highest: Cho Oyu, Everest, Lhotse, and Makalu. The Khumbu region, famous for trekking, is located at the southwest end of Everest. The Arun River drains the slopes of these hills, before turning south and entering Makalu’s eastern side. To the east of Nepal, the Himalayas rise in the Kangchenjunga massif on the Indian border, the third-highest mountain in the world, the highest in the east at 8,000 m (26,000 feet), and the highest in India.

The eastern part of Kangchenjunga is in the Indian state of Sikkim. The first independent city lies on the road from India to Lhasa, Tibet, which passes through the Nathu La pass to enter Tibet. To the east of Sikkim lies the ancient Buddhist kingdom of Bhutan. The highest mountain in Bhutan is Gangkhar Puensum, which is also a strong contender for the title of the highest mountain in the world. The Himalayas here become more fragile, and the valleys are steep and densely forested. The Himalayas continue, turning slightly northeast, through the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh and Tibet, before reaching its eastern end at the top of Namche Barwa, in Tibet, in the great waters of the Yarlang Tsangpo River. Beyond Tsangpo to the east is the Kangri Garpo Hill. The high mountains in the Tsangpo range, including Gyala Peri, also join the Himalayas at times.

Going west from Dhaulagiri, western Nepal is relatively remote and has no high mountains, but it is home to Rara Lake, the largest lake in Nepal. The Karnali River originates in Tibet but flows through the center of the region. In the west, its border with India follows the Sarda River and is the trade route to China, while on the Tibetan Plateau is the peak of Gurla Mandhata. Right next to Lake Manasarovar is the holy mountain of Kailash in the Kailash Ranges, which is near the source of the four rivers of the Himalayas and is revered by Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism, Sufism and Bonpo. In Uttarakhand, the Himalayas are divided into regions and the Kumaon and Garhwal Himalayas have high peaks of Nanda Devi and Kamet.

The state is also an important pilgrimage site of Chaar Dhaam, along with Gangotri, the source of the holy river Ganga, Yamunotri, the source of the river Yamuna, and the temples of Badrinath and Kedarnath. India’s next Himalayan state, Himachal Pradesh, is famous for its hill stations, especially Shimla, the summer capital of the British Raj, and Dharamsala, the center of Tibetan civilization and political power in India. This region marks the beginning of the Punjab Himalayas and the Sutlej River, which is the eastern branch of the Indus, passes through here. To the west, the Himalayas are much of the disputed Indian territory of Jammu and Kashmir, while the mountainous Jammu and Kashmir valleys are famous for the city and lakes of Srinagar. The Himalayas are the most southwestern part of the disputed Ladakh region, administered by India.

The twin peaks of Nun Kun are the only peaks over 7,000 m (4.3 mi) on this side of the Himalayas. Finally, the Himalayas reach their western peak at the impressive 8,000 m peak of Nanga Parbat, which rises more than 8,000 m (26,000 ft) above the Indus Valley and is the highest point in the valley. the sun of 8,000 m high. The sunset ends at a beautiful place near Nanga Parbat, where the Himalayas meet at the border of the Karakoram and Hindu Kush, in the disputed Gilgit-Baltistan region, which is administered by Pakistan. Parts of the Himalayas, such as the Kaghan Valley, Margalla Hills, and Galyat Territory, spread to the Pakistani region of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Punjab.

Hydrology

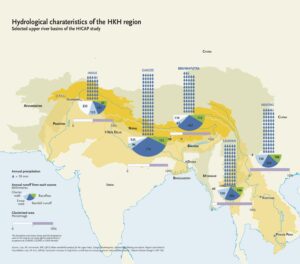

Despite their size, the Himalayas do not form a major continental divide and many rivers cross the border, especially in the eastern part of the range. Hence, the source of the Himalayas is not well defined and the foothills are not as important for crossing the border as the other foothills. The rivers of the Himalayas flow into two main streams.

The rivers in the west join the Indus basin. The Indus itself forms the northern and western boundary of the Himalayas. It begins in Tibet, at the confluence of the Sengge and Gar rivers, and runs northwest through India to Pakistan before turning southwest to the Arabian River. It is fed by several sources that flow from the southern slopes of the Himalayas, including the Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej rivers, the five rivers of Punjab.

Other Himalayan rivers flow into the Ganges-Brahmaputra. Its main rivers are the Ganges, Brahmaputra Yamuna, and other regions. The Brahmaputra rises below the Yarlung Tsangpo River in western Tibet and flows east through Tibet and west through the plains of Assam. The Ganges and Brahmaputra meet in Bangladesh and flow into the Bay of Bengal through the world’s largest river delta, the Sunderbans.

The slopes of Gyala Peri and the mountains beyond Tsangpo, sometimes included in the Himalayas, flow into the Irrawaddy River, which rises in eastern Tibet and flows south through Myanmar to throw into ‘The Andaman Sea. The Salween, Mekong, Yangtze, and Yellow Rivers all originate from parts of the Tibetan Plateau which are geographically separate from the Himalayas and are therefore not considered Himalayan rivers. Some geologists call all the rivers together as the rivers surrounding the Himalayas.

- Glacial

- Lekha

Glacial

The Himalayas, often referred to as the “Roof of the World,” are not only a majestic mountain range but also a crucial source of freshwater for millions of people across Asia. Glaciers, formed by the accumulation and compaction of snow over centuries, play a vital role in maintaining the region’s ecological balance and providing water for agriculture, drinking, and hydropower generation. However, the Himalayan glaciers are under threat due to climate change and human activities.

Rising temperatures have accelerated the melting of Himalayan glaciers, leading to concerns about water scarcity, natural disasters, and ecosystem disruptions. The loss of glacial ice not only affects downstream water availability but also increases the risk of glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs) and landslides, posing significant challenges to communities living in the region.

The Himalayan glaciers also contribute to global sea-level rise, as melting ice releases water into the oceans. This has far-reaching implications for coastal areas and low-lying islands worldwide, highlighting the interconnectedness of climate change impacts across regions.

Efforts to monitor and mitigate the impacts of glacier retreat in the Himalayas are underway, including scientific research, community-based adaptation initiatives, and international collaborations. These efforts aim to enhance understanding of glacial dynamics, develop early warning systems for natural hazards, and promote sustainable water management practices in the region.

Protecting the Himalayan glaciers requires concerted global action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, mitigate climate change impacts, and support adaptation measures for vulnerable communities. Preserving these iconic ice giants is not only essential for the Himalayan ecosystem but also for the well-being of millions of people who depend on them for their survival.

Lekha

“Himalayas Lekha: A Majestic Journey Through the Roof of the World”

The Himalayas Lekha, or Himalayan Range, stands as a majestic symbol of nature’s grandeur and resilience, stretching across five countries—India, Nepal, Bhutan, China, and Pakistan. This awe-inspiring mountain range often referred to as the “Roof of the World,” is home to some of the tallest peaks on the planet, including Mount Everest, the highest point on Earth.

Traversing the Himalayas Lekha is not merely a physical journey; it’s a spiritual odyssey, offering travelers a profound connection to the natural world and a glimpse into the ancient cultures and traditions of the Himalayan region.

As one embarks on this remarkable journey, they encounter a tapestry of landscapes, from snow-capped peaks piercing the sky to lush green valleys teeming with life. The Himalayas Lekha is also a sanctuary for diverse flora and fauna, harboring rare species like the snow leopard, Himalayan blue sheep, and red panda.

Throughout history, the Himalayas Lekha has captured the imagination of adventurers, mountaineers, and seekers of enlightenment. Its towering summits and treacherous terrain present both challenges and rewards, beckoning intrepid souls to test their limits and discover the depths of their resilience.

But beyond its physical allure, the Himalayas Lekha holds a deeper significance—a spiritual resonance that transcends time and space. For centuries, sages and mystics have sought solace and enlightenment amidst these towering peaks, drawn by the region’s profound silence and spiritual energy.

As travelers journey through the Himalayas Lekha, they are enveloped in a sense of reverence and wonder, humbled by the magnitude of nature’s creation. They encounter remote villages and monasteries clinging to mountainsides, where ancient rituals and traditions have been preserved for generations.

From the rugged landscapes of Ladakh to the serene beauty of Nepal’s Annapurna region, each corner of the Himalayas Lekha offers a unique and unforgettable experience. Whether trekking along ancient trade routes, meditating in mountain retreats, or simply gazing in awe at the towering peaks, every moment spent in the embrace of the Himalayas Lekha is a testament to the enduring power of nature and the human spirit.

In the heart of the Himalayas Lekha, amid the icy peaks and whispering winds, one finds not only the highest mountains on Earth but also the deepest truths of existence—a reminder of our interconnectedness with the natural world and the infinite possibilities that lie within.

Climat

The Himalayas, the world’s highest mountain range, boast a diverse and complex climate influenced by its vast expanse and varied topography. While the climate can vary significantly depending on altitude, location, and time of year, the Himalayas generally experience three main seasons: summer, monsoon, and winter.

During the summer months, from May to September, the lower elevations of the Himalayas experience warm to hot temperatures, with daytime highs ranging from 20°C to 30°C (68°F to 86°F). At higher altitudes, temperatures are cooler and more pleasant, making it an ideal time for trekking and mountaineering. However, summer also brings the risk of occasional thunderstorms and rainfall, particularly in the lower valleys.

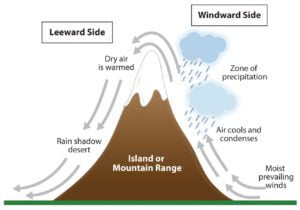

The monsoon season, from June to September, brings heavy rainfall to the Himalayas, replenishing rivers and lakes and sustaining the region’s rich biodiversity. The southern slopes of the Himalayas, facing the Indian subcontinent, receive the bulk of the monsoon rains, while the northern slopes experience relatively drier conditions. Rainfall can be intense, triggering landslides and flooding in vulnerable areas.

Winter in the Himalayas, from October to April, is characterized by cold temperatures and occasional snowfall, especially at higher altitudes. Daytime temperatures can range from sub-zero to 10°C (14°F to 50°F) in the lower valleys, while temperatures at higher elevations can drop well below freezing. Winter is an excellent time for snow sports like skiing and snowboarding in popular destinations like Gulmarg in Kashmir and Auli in Uttarakhand.

The Himalayas also exhibit microclimates, with significant variations in weather patterns over short distances. The southern slopes, influenced by the Indian Ocean, tend to be more humid and receive higher rainfall, while the northern slopes, sheltered from the monsoon by the towering peaks, are drier and experience less precipitation.

Overall, the climate of the Himalayas is characterized by its extremes, from scorching summers to frigid winters, with the monsoon providing a crucial source of water for the region’s ecosystems and communities. Understanding the Himalayan climate is essential for travelers and adventurers seeking to explore this majestic mountain range and its awe-inspiring landscapes.

Temperature

The Himalayas, often referred to as the “Roof of the World,” boast a wide range of temperatures due to their vast altitude variations and diverse climatic zones. Here’s a brief overview of the temperatures you can expect in the Himalayas:

High Altitude Regions: At high altitudes, such as those found in the higher reaches of the Himalayan range, temperatures are typically colder, with sub-zero temperatures common throughout the year. In the winter months, temperatures can plummet to extreme lows, sometimes reaching as low as -30°C (-22°F) or even colder, especially in areas above 4,000 meters (13,000 feet). Summer temperatures in these regions remain cool, with daytime temperatures ranging from 0°C to 15°C (32°F to 59°F).

Lower Altitude Regions: In lower-altitude regions of the Himalayas, such as foothills and valleys, temperatures are generally milder compared to high-altitude areas. Winter temperatures can still drop below freezing, particularly at night, but daytime temperatures typically range from 10°C to 20°C (50°F to 68°F). Summers in these areas are warmer, with daytime temperatures ranging from 20°C to 30°C (68°F to 86°F) or higher, depending on the specific location and elevation.

Transitional Seasons: During the transitional seasons of spring and autumn, temperatures in the Himalayas can vary widely. Spring brings gradual warming after the cold winter months, with temperatures slowly rising and snow melting at higher elevations. Autumn sees temperatures gradually cooling down after the warmer summer months, with crisp, clear days and chilly nights, especially in higher altitude areas.

Monsoon Season: The monsoon season in the Himalayas, typically from June to September, brings heavy rainfall to the region, particularly in the foothills and lower valleys. While temperatures may remain relatively mild during this time, the humidity can make it feel hotter than it actually is, especially in lower-lying areas.

Overall, the temperatures in the Himalayas vary greatly depending on factors such as altitude, location, and season. Whether you’re exploring snow-capped peaks, verdant valleys, or bustling towns and villages, being prepared for a wide range of temperatures is essential for enjoying all that the Himalayas have to offer.

Climat Chang

The Himalayas, the world’s highest mountain range, are experiencing significant impacts from climate change, posing challenges to both the environment and communities dependent on these majestic peaks. Here’s a brief overview of the climate change effects in the Himalayas:

Glacial Melting: The Himalayan glaciers are rapidly retreating due to rising temperatures, affecting water availability in the region. Glacial meltwater is a vital source of freshwater for millions of people in South Asia, and its decline threatens water security, agriculture, and hydropower generation downstream.

Altered Weather Patterns: Climate change is disrupting weather patterns in the Himalayas, leading to more frequent and intense extreme weather events such as floods, landslides, and avalanches. Erratic rainfall patterns and unpredictable monsoon seasons exacerbate risks for communities living in the region.

Loss of Biodiversity: The Himalayan ecosystems are home to a diverse array of flora and fauna, many of which are vulnerable to climate change. Rising temperatures, changing precipitation patterns, and habitat loss threaten the survival of species such as the snow leopard, Himalayan brown bear, and various alpine plants.

Impact on Livelihoods: Climate change is adversely affecting the livelihoods of mountain communities dependent on agriculture, forestry, and tourism. Reduced water availability, crop failures, and increased natural disasters pose economic challenges and food security risks for vulnerable populations in the Himalayan region.

Health Risks: Climate change in the Himalayas also brings health risks, including the spread of vector-borne diseases, waterborne illnesses, and respiratory ailments due to air pollution. Changing weather patterns may also affect the availability of medicinal plants traditionally used by local communities for healthcare.

Global Implications: The Himalayas play a crucial role in regulating the Earth’s climate system and water cycle. Melting glaciers contribute to sea-level rise, impacting coastal areas worldwide, while changes in weather patterns affect regional and global climate variability.

Addressing the impacts of climate change in the Himalayas requires coordinated efforts at local, national, and international levels. Initiatives such as sustainable land management, climate-resilient infrastructure, conservation of biodiversity, and community-based adaptation strategies are essential to safeguarding the Himalayan region and its inhabitants for future generations.

5 thoughts on “Himalayas”